Recipes in the Age of Meme Capitalism

A Line Cook's Rant about Recipes... Again.

Hi and welcome to everyone new here and to those of you who’ve been knocking around these parts a while, I’m so grateful you’re still with me.

This week, another in my (occasionally ranty) essay series.

For those of you here for the recipes, good news! Next week I’m sending all subscribers a recipe for Basque cheesecake I’ve been testing, made with an offensively delicious Norwegian ingredient called mysost (I checked, it’s available worldwide). It’s caramelly, rich but tangy, and hauntingly good in creamy desserts. You’ll love it.

And for paid subscribers, The Prep List continues soon.

This is my book serialisation: a line cook’s handbook for home cooks.

Over the next year, you’ll get chapter-by-chapter insights drawn from everything I’ve learned during my years in professional Nordic kitchens, all made doable at home. Each chapter focuses on one subject, so you can cook with more confidence, more ease, and, I hope, more creativity.

Upgrade today to join The Prep List and support this newsletter.

Now, onto this week’s essay…

How to lose friends and alienate other line cooks

There are countless ways of making a bad first impression when you start a new restaurant kitchen job, and one of the most ubiquitous is to never shut up about how you did something “at your old restaurant”.

No one will care, I promise you, and the more you do it, the more insufferable your new colleagues will find you.

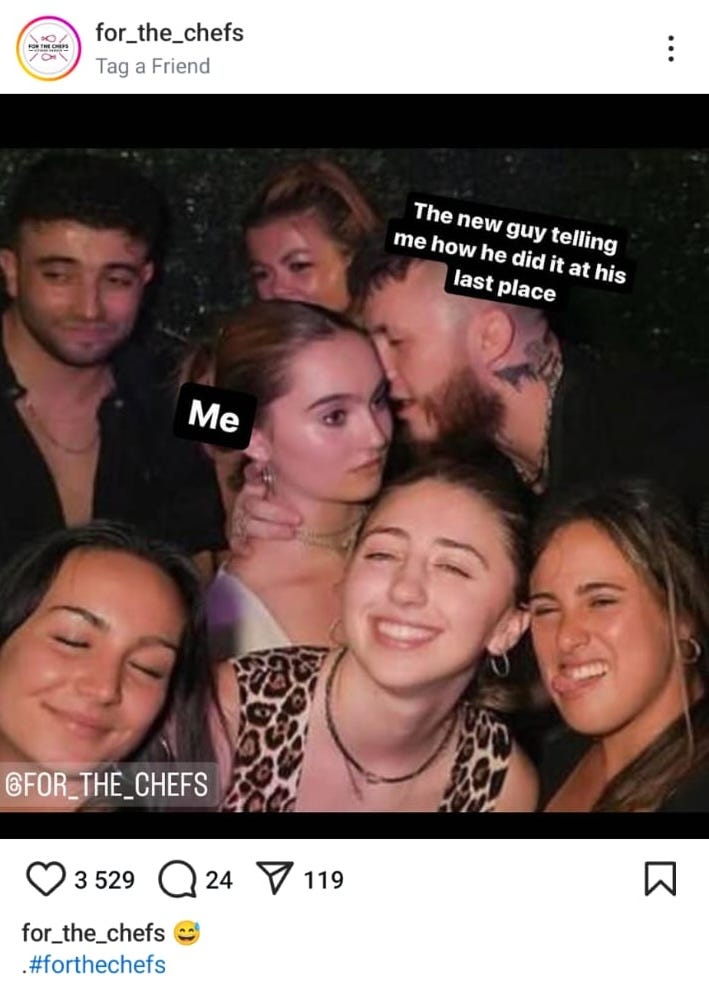

Despite this truth, it’s such a common thing for new hires to do (Christ, I’m sure I was guilty of it in the early days1), that it’s become something of a meme in that subversive corner of social media focussed on kitchen worker content.

It doesn’t take a rocket surgeon to understand why it’s annoying. Kitchens are busy places. When we’re trying to teach a new cook “our” way of doing something, interruptions about whatever esoteric way their former head chef boiled eggs are a hell of a time waster.

All that said, the suggestions being offered are never (in my experience at least) couched in terms of “this is my way, I know best”. Instead, it’s always attributed to the old workplace, an old colleague. It always seems a generous act this way, not about inflating their ego at all.

I’ve been thinking of this small “chef life” idiosyncrasy the past week or so having read the fuss about a baking influencer accused of stealing recipes for their multi-million-selling cookbook in Australia.

If you’re interested, you can read the accusations here. But what interests me enough to bother your inbox about it today is the larger idea in question here: how are recipe writers supposed to attribute things? Can recipes be protected or owned? Should they be, even? And, whose job would it be to enforce? Law or moral obligation?

Tread softly because you tread on my memes

It was either Steve Jobs or Dick van Dyke who said:

"It’s not about being first. It’s about being the best."

I’m reminded of this whenever I scroll through my Instagram and TikTok feeds.

I recently started posting short videos to these platforms in my ongoing attempt to make the world aware of the joys of The Recovering Line Cook (sorry to those of you who think such behaviour is trashy for such an esteemed newsletter writer as myself, but I am very trashy, darlings).

What I’ve learned is that these platforms really try to take the work out of creating content. Free in-app editing tools both make it easy to find other videos for inspiration that have already performed well, and in some cases offer templates for you to quickly recreate those videos as well.

It’s no surprise then that creator after creator are doing the same thing as each other. The same joke, the same dance, the same punchline, the same music.

It’s actually pretty impressive how such little original creative thought can amount to the huge online followings and fanbases you see on these platforms.

It makes me realise that, nowadays at least, it’s not about being first, it isn’t even about being best, maybe the important thing is just, well, being.

Very occasionally the person who believes they were first gets upset about their imitators who’ve stolen their words/audio/concept, particularly if any of the “thieves” have big followings. A video might follow, likely “calling them out”, but what’s to be done? Social media doesn’t work along rules of footnotes and annotation and attribution. Things on these platforms move too fast for that.

And this is no less the case for short form video food content.

You may have heard something hinting at this habit from food creators in words to the effect of “I had to jump on this trend” when sharing a recipe. It’s so often a trend, not a recipe. Not a product of a living, breathing recipe developer or writer. Eventually this becomes unavoidable. The trend becomes so divorced from its creator that it becomes meme itself.

My guess is that’s just the way billionaire owners of these huge platforms like it. Engaging content rises to the top, it keeps people on platform, and can then be freely recreated by others to start the loop over again.

Meme capitalism

One of the more surprising tech-bro fantasies I hadn’t seen coming in 2025 is the idea of treating substantial creative work (books, films, art) as if it were as free and uncopyrightable as memes.

I’m no Thomas Piketty, but even I can see how strange it is that intellectual property, once seen as a cornerstone of creative ownership, is now framed as an obstacle to capitalist free enterprise. As the linked article explains, figures like Twitter founder Jack Dorsey and Twitter annihilator Elon Musk have been open about wanting to “reform” IP laws to make it easier to harvest books and other media to train AI models. You don’t have to stretch your imagination to see why the “meme model,” where nothing is owned and everything can be repurposed, is so appealing to them.

From their perspective, IP is a bottleneck. Author ownership slows growth and hampers the endless “repurposing” of content. In a world built on frictionless content and the drive to “scale,” even basic attribution is an inconvenience.

Francis Coulson’s Strawberry Pots de Creme

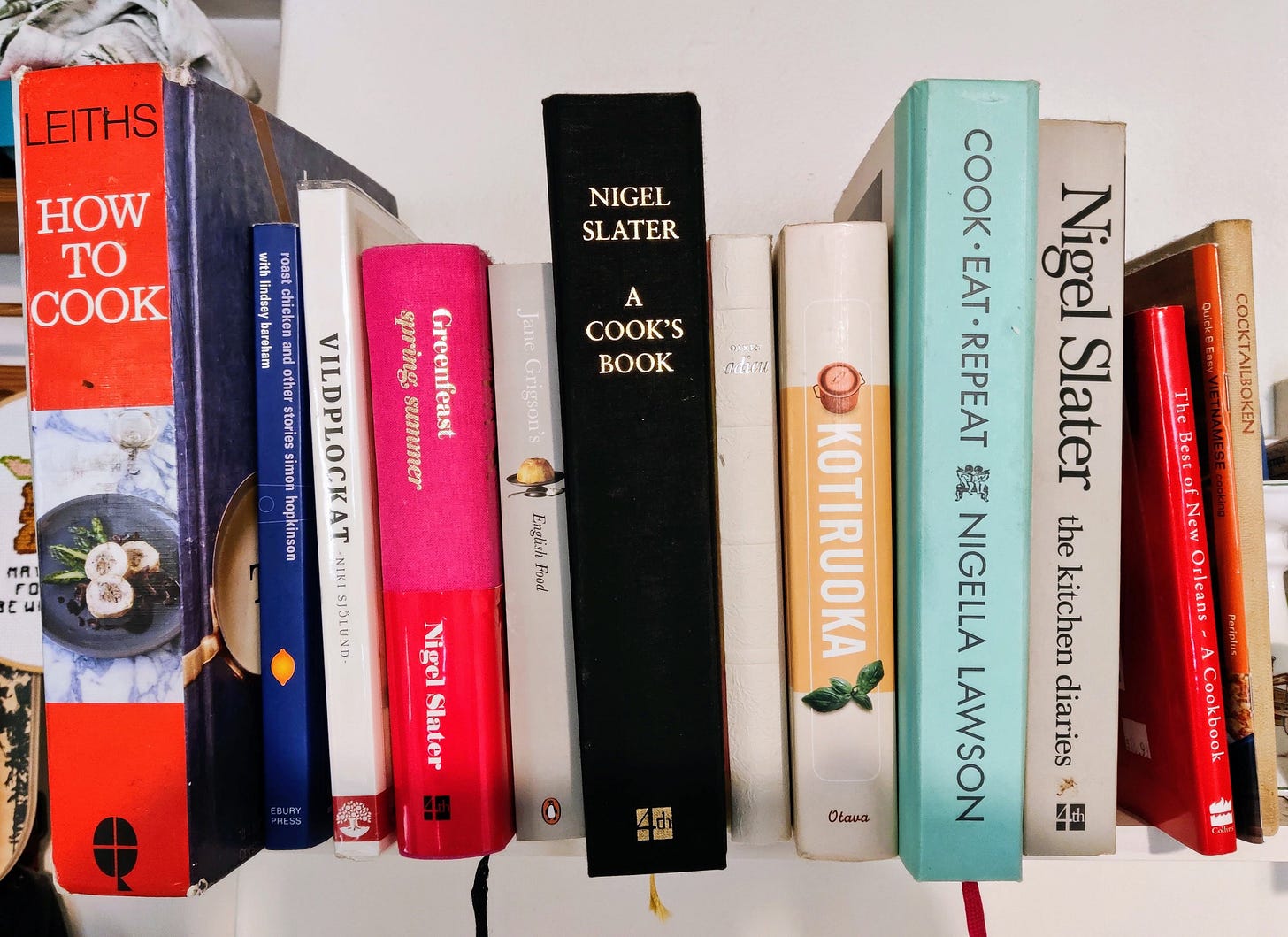

With this all in mind, I flicked through a few of my favourite, classic cookbooks as I started putting this piece together to see how my heroes did things in years gone by.

Did they only ever talk about themselves? Did they make on that all their knowledge was summoned from the majesty of their own genius? Or did they, rather, manage to find space to attribute something to where they might have learned it?

The very first 2 books I picked up gave me an answer.

On almost every page of English Food by Jane Grigson and Roast Chicken and Other Stories by Simon Hopkinson with Lindsey Bareham, the authors never shut up about… wait for it… people other than themselves!

They attribute recipes to their friends, old colleagues, restaurants they’ve visited, and, of course, books they love.

Those who argue recipes are uncopyrightable often suggest this is because they are straightforward factual accounts of how to do something.

A mayonnaise can only be invented once, after all.

And yet, when sharing something as simple as a 5 ingredient Pots de Creme, Hopkinson and Bareham don’t name their recipe simply “Strawberry Pots de Creme”, they call it:

“Francis Coulson’s Strawberry Pots de Creme”

and that they

“first came across [the recipe] in a (sadly) forgotten book called The Good Food Guide Dinner Party Book.”

IT WAS A “FORGOTTEN BOOK” FFS, MY GUY SIMON COULD HAVE NABBED IT FOR HIMSELF SO EASILY!!

And I could list endless recipes from the Grigson that treat her many sources just the same.

There simply seems a standing and natural desire to detail their inspiration in these books. It’s like an obsession for them.

In contrast, I read a “new” recipe for burnt basque cheesecake recently. It wasn’t from a big-name writer so I won’t link him or give his name. My anxiety is way too bad to start creating online beef with this newsletter. What struck me about the piece was how he made a point of having never made a cheesecake before, and, though he made it his own by adding a slightly left-field flavouring, the one shared in the blog was his very first.

My natural reaction as a restaurant cook to (want) to ask was: whose recipe is it you’re sharing then? Surely you didn’t invent the balance of cream cheese, eggs etc from scratch? Isn’t this kind of information something we should expect?

Yet another contrast are food creators like Joshua Weismann. A few months back, Weismann, one of the most popular and financially successful food creators to have taken the Youtube to Instagram to published cookbook route, gave an interview in which he said something that genuinely shocked me.

In the interview, Weismann turns his attention to “fellow” (my word, I assure you) online food creators. He talks of intending to “steamroll the fuck” out of other creators who come in to his “space” and how thoroughly he will “outwork” them and (shudder) “bust their ass”.

I mean, good grief! How exhausting it must be to think this way. I wonder if he ever references other people in his recipes?

What’s your guess?

Does listing footnotes, attribution, any evidence at all we relied on someone else in order to create something not give the “vibe” we want in this personality-centric age?

Is sharing our platform even slightly something we can’t afford to do? Is the risk someone clicks away from our platform to those we footnote too great?

Alicia Kennedy helped set me off on this line of thought when she posted on a social media account recently:

No, Kennedy isn’t talking about recipe writers here, but I wonder if the same “creator” mentality is part of the problem.

Meme capitalism demands speed, social media prioritises personalities who are imbued with authority, and audiences want simple narratives. We want our favourite personality to tell us what’s good, and we want it to be their idea, not some random idiot we don’t like/share/subscribe to.

Maybe I’m being difficult. Maybe some recipes are simple science. Maybe the guy I referred to earlier really did work out the precise measurements for cheesecake without the input of anyone else. Besides, even at the classical London culinary school I went to, we were taught it took just 3 ingredient changes to make a preexisting recipe our own. That feels like a three-course meal of horseshit thinking about it now. Something is lost if we treat another person’s recipes this way. And I treasure the fact writers like Grigson and Hopkinson don’t simply put themselves front and centre leaving readers to assume it’s all their work.

Instead, they help share the full picture and give the bigger, and so much better, insight into how a dish was created. The story behind it. The reason for its existence.

When we don’t do that, writers and social media creators alike, recipes become little more than memes, and we become cogs in this frightening new stage of capitalism that threatens to take author rights away to feed an ever-turning, AI-empowered content machine.

Mother sources

The more I think about this, the more I think recipe blogs and cookbooks have got an easy pass. Lazy, even. Any great non-fiction book, filled with fascinating novel insights, will still be full of enriching, illuminating and enjoyable footnotes and sources that show the genealogy of their new ideas. This is not a contradiction! Why can’t cookbooks consistently do the same? I for one, though not asking anyone to rip me off, would be more than happy to see someone riffing off a recipe I came up with. All I’d ask for is a hattip (and a working backlink, OK, I got kids to feed!)

If it is good enough for Jane Grigson, and those dear line cooks who don’t shut up about how their old head chef used to make cartouches, it should be good enough for any of us.

A final note

I want to offer a friendly “up yours” to those insufferable people that comment that a writer’s headnote/headessays/headmemoir is “too long” and that they need to “get to the recipe quicker”.

That “irrelevant detail” at the beginning is:

Often the real reason we share recipes at all, and,

All we have in the fight against the growing repository of AI-generated recipes stolen from real writers’ work.

Private online cooking classes now open

I am really excited to be starting online cooking classes this summer, and I am making them available to readers of my newsletter first at a 50% discounted launch rate.

My hope is these sessions will be great for anyone who enjoys my writing, is interested in learning a thing or two about great cooking through a Nordic lens, or just wants a fun, 90 minute session via video call to go through a particular subject or even recipe of mine.

I also think they’d be a great gift for any young cooks/students in your life who might want to benefit from my experiences in restaurant cooking.

Click below to find out more or please simply reply to this email if you have any questions!

Further reading

Since I wrote this week’s essay, I saw the wonderful Diana Jacobs covering the topic with a little extra insight into the specific copyright issue of the day here. Check out her insights and practical offerings for writers, as always she is a joy to read.

Also, a NYT article from a few years back on the subject is definitely worth a read as well on the basis it heavily features the wonderful Andrea Nguyen and offers some really great advice and insights from her.

The Prep List continues…

The next instalment of my serialised “narrative cookbook”, The Prep List, will be going out exclusively to paid subscribers soon.

After a leisurely forage in chapter 1, in this next instalment we’ll be setting up for our 16-hour shift of cooking, and looking at both the practical things restaurant cooks do to make cooking more organised, and the mindset that helps them achieve so much so quickly.

This is a subject I find fascinating and I’m really enjoying putting down these productive insights to share with you.

If you’d like to read it, and get access to all my writing, please upgrade and become a paid subscriber today!

I am insufferable but long-time readers of mine will know this, obvs.

As someone who reads a cookbook as though it’s a novel, I love the headnotes and can’t understand this trend towards shorter/fewer/no headnotes on recipes. Where else would I learn about the cook’s inspiration, or methodology? Or even alternate cooking suggestions if, say, I live in a different country than the author and cook with gas and not electric or what have you? The best books have the best headnotes that tell me about the cook’s inspiration behind the recipe—which tells me more about the recipe than a list of ingredients could ever do alone. Just my opinion, but I’d be less inclined to pick up a book that was thin on the notes. I love the personality and backstory that comes through, and yes, the attribution!

You just have to watch something like British Bake Off to see there’s very little true innovation in recipes. The chemistry of a recipe works with certain ratios and functional ingredients, so you’re really quite limited. Innovation may be a lot to do with presentation.

I’m an IP professional. Not so much copyright, but that does seem to be the only protection for a recipe, although patents are full of recipes of one kind or another, not necessarily food.

If I was to publish a cookbook, the least I could do was say where I saw it or ate it, even if I made alterations to it. You have to give some attribution. Must give…