The Prep List: An Introduction

Finding the Correct Dosage

An introduction: Finding the Correct Dosage

There’s this American sitcom you may have heard about called Scrubs. It ran years ago now and, when I was a kid, I thought it was hilarious. The show tells the story of a group of fresh-faced medical interns as they get their heads around life as doctors in a busy hospital. At the heart of everything is J.D., the neurotic, passionately weird but well-meaning protagonist with an over-active imagination (yep, I guess I related to him). J.D. is a good guy, and he desperately wants to become a good doctor. But it’s also clear that what he really wants is to win the love and willing mentorship of his boss, the miserable, heart-of-stone, borderline alcoholic Residency Director, Dr Cox. A core part of the show’s comedy comes from Cox’s persistent rebuttal of J.D.’s affections. He just isn’t interested. The only thing that matters to him within those hospital walls is the patient. And the only way J.D. might ever really connect with him is by proving he cares about the patients just as much. A defining part of the series’ happy ending is seeing that finally happen in the form of a (nearly) affectionate hug the two doctors share.

You’ve probably heard life in a restaurant kitchen as likened to that of a soldier’s in the military. I really fucking hate this. It’s miserable to me that an act concerned so entirely with joy and well-being is associated with humanity’s self-designed death machine. “It’s only dinner”, a head chef I particularly enjoyed working with once told me, “everyone’s gettin’ outta here alive”. But even so, I’d much rather liken restaurants to hospitals than battlefields, particularly if my limited Scrubs-informed knowledge of them is anything to go by. That’s because, like J.D. and Dr Cox, the only thing any cook worth their salt is interested in is making people a little bit “better”. This might sound a bit wanky, if you’ll forgive the Britishism, but it’s true.

This is the reason why the measure of a cook is in how they work when no one is looking. Are you the kind of cook that takes the time to brown all the sides of the stewing meat to deep russet savouriness, or do you save yourself some bother, and bag an extra few minutes for lunch, by skipping that part of the gig? Whether you’re a young restaurant cook starting out or a seasoned pro leading others, greatness in the kitchen is as simple as that: are you the person who takes those few extra minutes to show you really care about the guest? Are you the kind of person Chef Cox would respect?

If it’s a yes, everything else will follow.

I love restaurants and I love cooking in them. But there’s no phrase I find less meaningful in the food world than “restaurant quality”. It manages to both disregard the enormous amount of shit, cynical, unforgivable restaurant food out there and suggest that home cooking is by definition second-rate.

You try my mother’s Yorkshire puddings and gravy and tell me that.

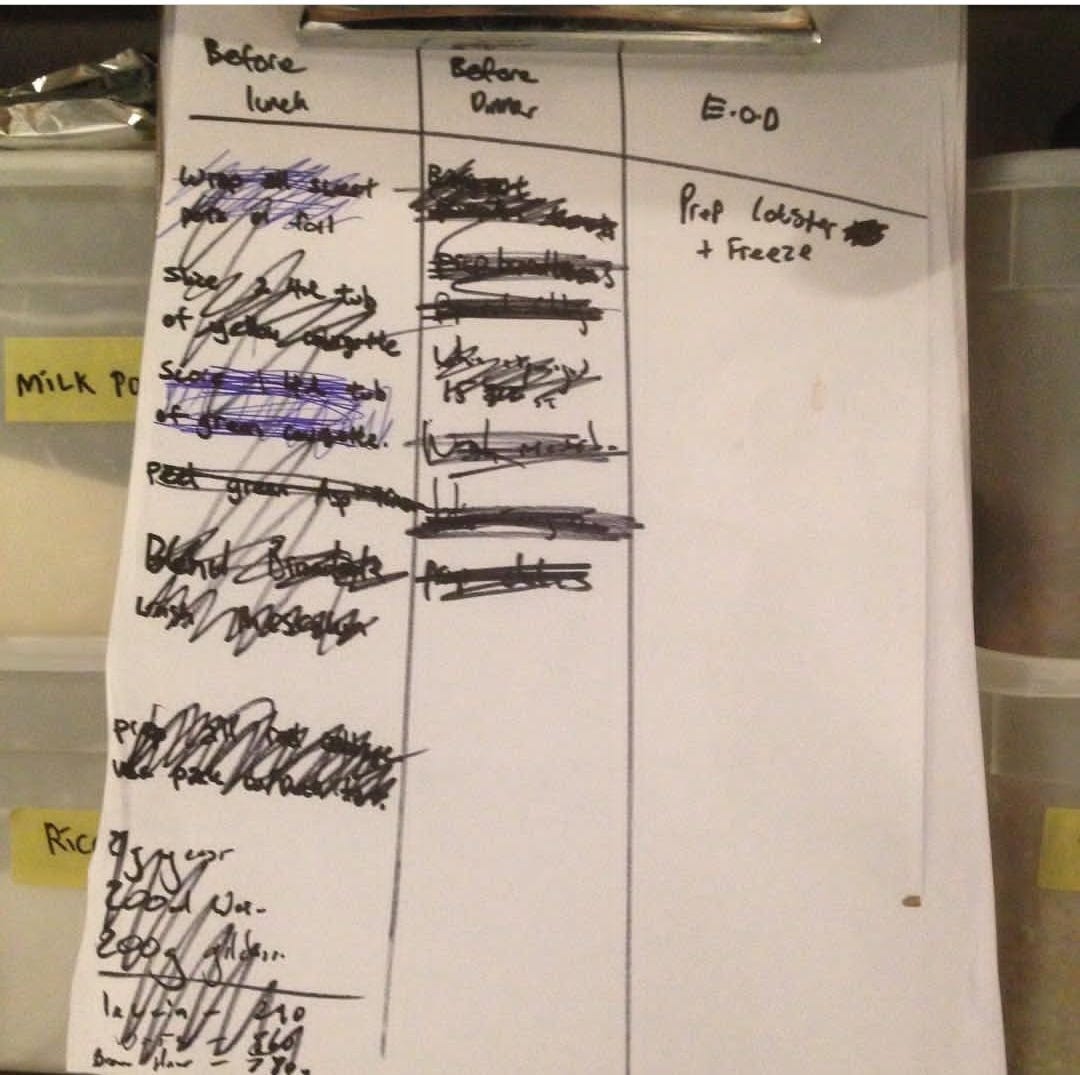

And yet I have decided to write a “book” that shows you an entire 16-hour shift of a restaurant cook so you can learn the ins and outs of how he works. Why so? Well, for one, this is a cooking world I know well. I’ve had several jobs and the one that’s filled me with most joy, achievement and satisfaction is that of restaurant cook. And what I have come to feel is that, though there is no inherent difference in quality between home and restaurant food, the efficiency, pragmatism and creativity on show in the best restaurant kitchens are things any passionate cook can benefit learning from.

I’ve been lucky enough to work in some truly great kitchens in London, Stockholm and my current home of Turku in Finland. And I’m only the cook I am today because of the people I’ve worked with. They taught me to never forget the guest, to always work to make dishes both new and old better, more delicious, more full of care. There is no hiding in a restaurant kitchen. If the recipe doesn’t work, it’s out. If the dish isn’t good enough, it’ll get “developed” until it’s better. If any dish is too technically esoteric that only the head chef with 50 years’ experience can make it, that’s no good either.

This brings me to why The Prep List is set in a living restaurant kitchen. Kitchens are wonderful places to learn. Though I went to culinary school, I feel my training really began when I stepped into the kitchen of a restaurant called Portland in central London for the first time. I’ve worked in some very different kitchens since then. But if there’s one thing they shared it was a rejection of the old-fashioned military brigade system that would have young cooks peeling potatoes for a year before being promoted to any more demanding tasks. The kitchens I worked in encouraged cooks of all levels to try new things, new skills, new responsibilities. And far from resulting in a drop in standards, it simply created a workplace where all cooks were challenged to learn efficiently and thoroughly.

This will be the environment I want to share with you over the following months of this newsletter and chapters of The Prep List.

I want to show you fewer rigid recipes and more living stories that give a feel of how I work and continue to learn in restaurant kitchens. I am writing these words in my small flat in Turku, Finland. To my left I have a bookshelf full of weighty and intimidating cookbooks. Many of these, written by lauded chefs from the world’s great restaurants, are testaments to one man’s decades of experience and knowledge. Decades of experience should never be a required “ingredient” in a cookbook, or at least not in any book I’m interested in writing. What I want to show in the following pages is how accessible great cooking is to everyone, just as it is (and needs to be) to a young line cook finding their way in their first restaurant job.

I mentioned I live in Finland. As a Brit, I’m by nature impressively shit at languages for probably obvious reasons, and learning Finnish continues to be a… struggle. But one thing I’ve come to realise learning the fundamentals of a new language is that it’s not all that different to learning the fundamentals of great cooking. The things I can say in Finnish are few compared to what I can babble about in English. But even with my limited Finnish vocabulary I can build sentences. I can take small blocks and, with a painful amount of concentration, build them into expressions of feeling and even of love. What I like to believe is that this ability to say as simple a thing as I love you in my wife’s native tongue is more meaningful to her than all the intricate and profound expressions of love I could recite in English a hundred Shakespeares could compose. And just as the most intricate sentences are constructed by the simplest words, so too is the most delicious food no more than a multitude of small things done well and done with care.

This is why I am so grateful for my experience cooking joyous but simple food here in Finland and Sweden.

The short, fertile summer yields incredible produce: musky cloudberries, astringent sea buckthorn, deeply-scented wild herbs like woodruff and pineapple weed. But winter looms, and survival has long depended on the ingenuity of preservation. Salt, smoke, and acid don’t just prolong the harvest; they define the flavours on the plate as well. The food may be simple declarations of the ingredient, but flavours are bold: pickling liquors sharpen buttery sauces, meats are deeply seasoned, and smoke and charcoal permeate so much.

By getting an insight into the flavours and techniques of the Nordic region, I believe you will learn things that can improve your cooking regardless of the cuisine you turn your hand to.

I feel like the day of our 16-hour shift is fast approaching. But first, a final word on recipes themselves.

Recipes are important in restaurant kitchens. They help keep things consistent, they make sure the guy who’s fucked his palate after a lifetime smoking and huffing poppers doesn’t oversalt the vinaigrette, and they help teach the youngest of cooks the basics of a dish. But they can only ever teach so much. A better way to learn is by doing. And the very best way to learn is by doing alongside a knowledgeable friend. It is my hope that The Prep List can offer you the next best thing by guiding you through a day in one of the wonderful restaurant kitchens I was lucky enough to learn and work in. I will lean into this story-driven approach over rigid recipes structured by precise lists of quantities and measurements in The Prep List. Doing this I hope to encourage and train your own instincts toward becoming an even better cook.

In this I am reminded of what is without question my favourite joke from the entire run of Scrubs.

J.D. is worried about how much of a simple, non-prescription medicine to give a patient.

Here’s how it goes down:

Dr. Cox: Did you actually just page me to find out how much Tylenol to give Mrs. Lensner?

JD: I was worried it could exacerbate the patient’s…

Dr. Cox: It’s regular strength Tylenol. Here’s what you do. Get her to open her mouth, take a handful, and throw it at her. Whatever sticks, that’s the correct dosage.

With so much in recipes I feel the same way as Dr. Cox here. Do you need to be told how many onions to use or cloves of garlic? It often seems so arbitrary. There’ll be no such dictation in The Prep List.

I hope you end up thinking that a good thing.

Being serialised as a part of my newsletter, I like to think of this as a “living” book. That’s why I think a contents list would be a little premature. But what I do want to share is something of a “sample menu” for the kinds of things we will be working toward creating for our Nordic menu. Being a sample, some of these dishes might change over the following months, but to get a sense of the techniques and skills we will be exploring as we go, hopefully this gives a good idea.

Burnt celeriac ”tartare” with ash mayo, and vendace roe

Sugar-salted trout with cultured dill cream and crispy skin

Ember-grilled scallop with yeast dashi

Slow-fermented bread with cultured butter and broth

Vegetables and dip

Lake fish with grilled butter hollandaise

Lightly-smoked deer, mille-feuille potato, parsnip puree and fermented berries

Pineapple weed sorbet

Parsnip cake with sea buckthorn glaze and caramelised whey ice cream

Chocolates and candies flavoured with foraged vegetables and mushrooms

No story ever really begins. Always there is something that came before, something that made the beginning possible. For the line cook we’re spending our 16-hour shift with (who looks and sounds much like me) what came before is a meagre few hours’ sleep following his previous shift. A new spring day has arrived and the sound of a deer barking outside his small Stockholm cabin has woken him moments before his alarm had a chance to.

Perhaps his bed, then, is where we can go to and begin…

ps

Everything you’ll read here is true, it really happened…

…especially the bits I made up.

Really into this lens already, love anything that gets under the skin of how restaurants actually work. Looking forward to reading more. There's so much happening behind the scenes that most people never clock! P.s. loved scrubs and currently rewatching all my favs.

The Blue Strawbery Cookbook (Cooking Brilliantly Without Recipes) – January 1, 1976, was a favorite of mine back in the day, as was Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly – January 9, 2007. Of course, Bourdain’s book was NOT a cookbook. Your post reminds me that these two books each had an impact on me.

I particularly enjoy books about cooking that encourage me to think about the big picture of flavors and how to achieve them. (Paul Prudhomme taught me about adding flavor to dishes by boiling shrimp heads.)

I believe baking is a science that is best understood by ratios that are fundamentally different from regular cooking. See also: Ratio: The Simple Codes Behind the Craft of Everyday Cooking (1) (Ruhlman's Ratios).

TMI, I’m sure. I can’t closely follow most recipes because I’m a frequent taster.

What flavors interest you? What’s special about your flavor palette?

Also, what’s different about being a founding member than being a subscriber?