Sick Mood at Sunset

Notes on my favourite painting

Whenever I miss my old home of Stockholm, the place I really miss is an island called Djurgården. Djurgården is where my wife and I would pick svart trumpetsvamp in autumn. It’s where we’d have picnics on fresh spring grass looking out to the blue Archipelago waters. It’s where I took my mother to see Elton John one summer at Gröna Lund. And it’s the island I spent countless hours cooking at a restaurant called Oaxen. When I miss my old home, I miss an island called Djurgården.

My family and I make the trip from Turku in Finland to Stockholm twice a year these days. We visit Djurgården every time. But with two kids now, most of our visits are spent at a wonderful children’s museum there called Junibacken; a play and exhibition centre dedicated to Swedish children’s literature.

There are many things I love about being a dad, one of them is having an excuse to visit Junibacken.

But were I to be honest, if I had it my way we’d visit a very different museum at the far end of the island. Here, in a building of white facades lidded with a turquoise roof of decades-old copper is the Thielska Galleriet, my very favourite museum.

Walking through Thielska, carpeted idiosyncratically and full of curious little rooms packed with diverse pieces of art, it feels more like visiting the mansion of a deceased early-twentieth century millionaire than a sterile gallery. And that’s likely because you are. As well as being a successful investor, Ernest Thiel also boasted a remarkable collection of works by Nordic artists, which he kept in his home on Djurgården.

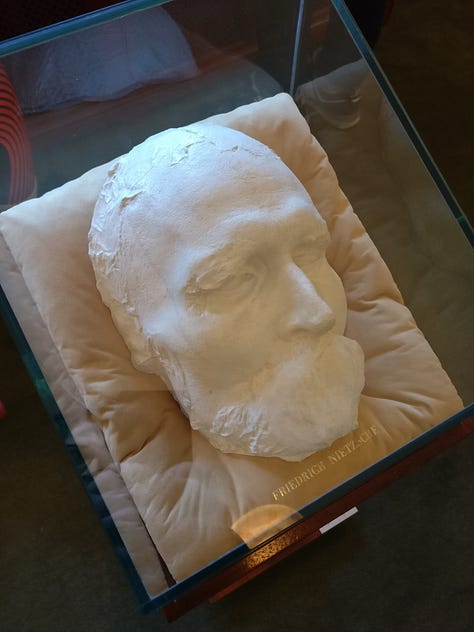

He was also passionate about Nietzsche. In one of two small turret rooms at the top of the building you’ll find Nietzsche’s death mask in a small glass case.

But it’s a painting in a room downstairs I’ve spent the most time with over the years. Nietzsche looms large over this room. His portrait, placed opposite the entrance on the far wall several metres high, is likely the first thing you see on entering. But his presence is outdone by that of another, unseen, man. That man is the artist of the paintings here: the Norwegian Edvard Munch. And if Thielska is my favourite gallery, it’s largely because next to Munch’s portrait of Nietzsche you’ll find my favourite painting.

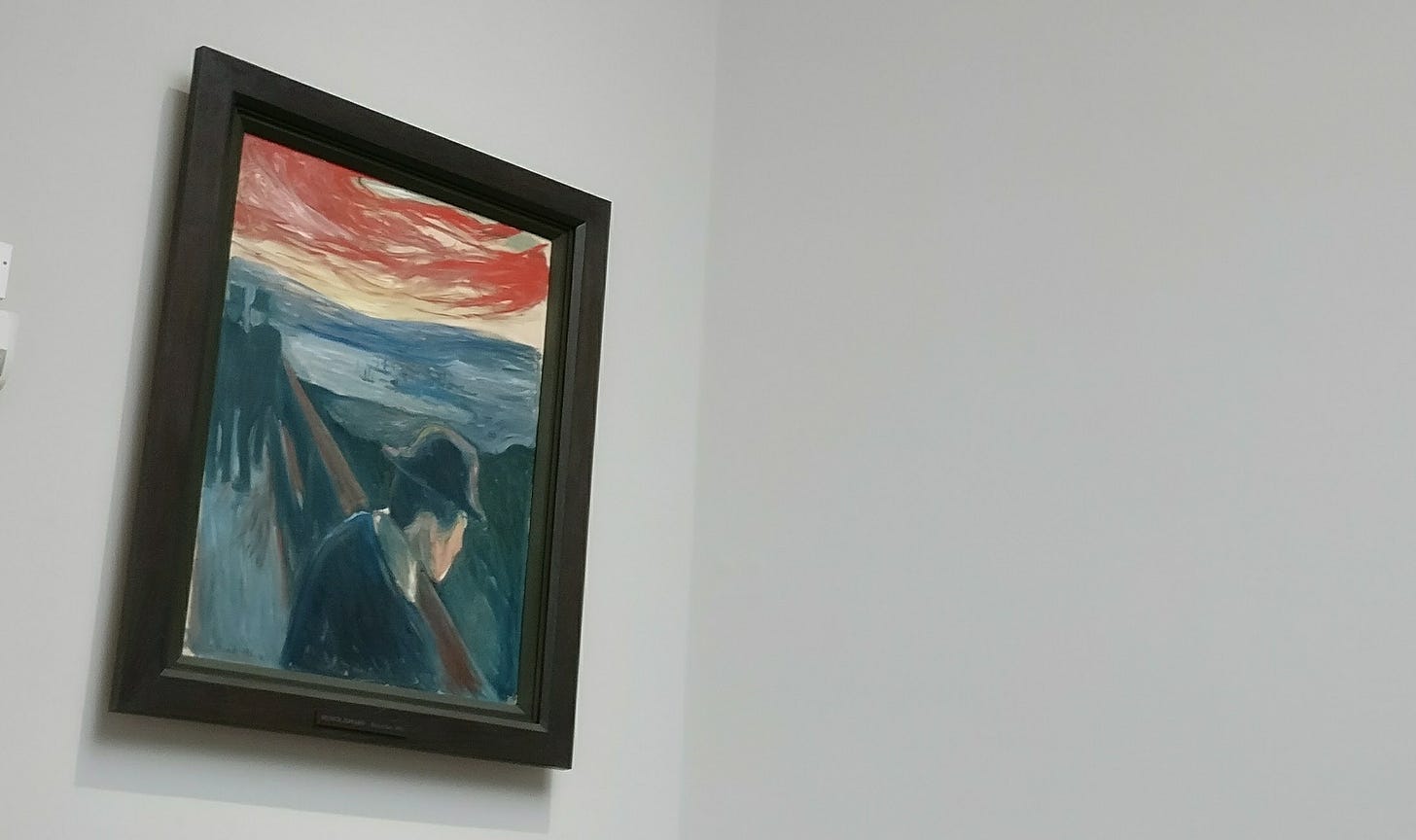

This painting is of a figure on a bridge. It stands alone with two other figures further along the bridge behind him. It’s as though they’ve abandoned him. Behind this lonely and desolate figure, the bridge looks out to hills that descend into a valley lake. Among the swirling colours and disorientating shapes that form the landscape, you can just make out boats on the water. They are illuminated by the violent blood red of the threatening sky.

Were it not for the lonely man, this would be among the most famous paintings in the world. The only thing that stops it being The Scream, a painting you’ve likely seen on countless coffee mugs and t-shirts and posters the world over, is that lonely man. He isn’t a distorted, abstract, barely human figure. He is a man in a business-like hat painted in as simple a way as the figure of The Scream is alien. Completed some years before The Scream, this painting is called Despair.

Munch’s modern, radical work, such as that which fills this room at Thielska, was considered “degenerate” by the Nazi Party. In an effort to bring art under their state control, such work was removed from galleries, some secretly burned, some disposed of by auction. 82 works of Munch’s in Germany were confiscated by the late 30s.

But it wasn’t enough for the Nazis to simply remove the work. They needed to make examples of it for their own ends as well. This is why in 1937 the Nazis held an exhibition of the very “degenerate” art they had confiscated. The goal being to educate the German people in how morally “impure” such art is and insulting to the “German values” the Nazis were trying to instil. In contrast to classical forms of beauty and moral worth, the art of modernity was “sick”. Slogans on walls alongside the art made this narrative clear. One declared the collected art showed “how sick minds viewed nature.”

Paintings can tell a story, I believe, just as much as the more traditionally narrative forms of art. And if narrative is the way in which we experience new and different perspectives, then that so-called “degenerate” art is as necessary to the world as the classical traditional forms many find comforting and familiar.

In the Thielska Gallery, that favourite painting of mine is labelled Despair (Swe: Förtvivlan). But that’s actually only the work’s shortened title. The full title is Sick Mood at Sunset. Despair. I feel something is gained by calling it this. Contrary to the tyrant who makes a value judgement of the sick, the degenerate, the abnormal, the foreign, the deviant, I feel Munch’s sick mood reclaims the term for an expression of nature and the world that is, to quote his neighbour on the Thielska wall, beyond good and evil.

When certain types of expression and life are associated with an accepted moral order, not corresponding becomes an act of resistance. With the inevitable despair the world may leave us in these days, I choose to feel this is why tyranny always has such an uphill struggle; the greater the list of unacceptable transgressions, the easier it is to resist.

This essay is dedicated to those who resist.

It's interesting how much it reminds of The Scream whilst being so very different. A faceless man on the bridge, quite intriguing.

I had somehow missed that you cooked at Oaxen. We went to Oaxen Slip when we visited Stockholm some years back!